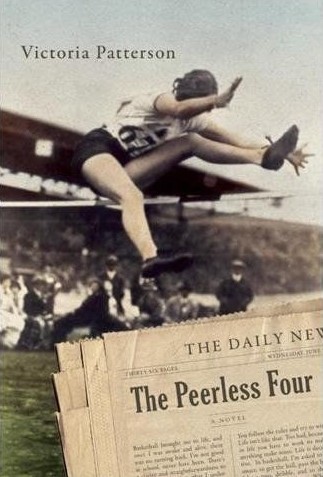

Victoria Patterson’s The Peerless Four is a sports novel for people who don’t really like sports.

Victoria Patterson’s The Peerless Four is a sports novel for people who don’t really like sports.

It’s also the most cautious and measured novel I’ve read in a while, quickly establishing its tension with two epigraphs: The first (familiar) quote tells us that “it’s not whether you win or lose but how you play the game,” whereas the second quote argues that there isn’t “any point in playing the game if you don’t win.”

Patterson’s novel begins in 1928 and follows the progress of the first all-female running team—nicknamed The Peerless Four—to participate in the Olympics. The novel opens with each of The Peerless Four introducing herself to the reader in brief, first-person chapters: Florence Smith has battled her father over her athletic ambitions; Bonnie Brody has fallen in love with her coach; Ginger Hadley is fragile and beautiful; and Muriel “Farmer” Ziegler has spent her life trying to compete with boys. Each has something to prove, and occasionally Patterson lapses into sports novel clichés like when, in Farmer’s voice, she writes, “After that, I went after everything full force, whether I won or not.”

Eventually, Marybelle Eloise Lee (Mel) takes over as the novel’s narrator. Mel chaperones The Peerless Four to the Olympics, invited along by the team’s manager, Jack Grapes, who smokes, drinks, and is just about as hardboiled as you’d imagine a guy named “Jack Grapes” would be in 1928. In his treatment of The Peerless Four, Jack alternates between sexism and paternal kindness. He’s aware that most people see female athletes as oddities. He might even agree.

But Mel, not The Peerless Four nor Jack, is the center of the novel. A reporter, Mel follows the progress of the team, from Jack’s attempts to charm the girls’ skeptical parents, to the Olympics in Amsterdam, where Mel has to navigate and disarm the jealousies, insecurities, resentments, and superstitions of the athletes.

At first, Mel narrates in a journalistic tone, and Patterson uses this smartly, sketching out how Canada feels about The Peerless Four. Journalists dote on beautiful Ginger (one small but telling moment finds photographers posing Ginger with her dog for candid shots) and gawk at masculine Farmer (“One forgets that he is watching a girl”), while editorial writers argue that allowing women to compete at the Olympics is a moral obscenity. In this way, The Peerless Four resonates with our current moment. Sexism still saturates our media, and Patterson shows an earlier version of something sadly familiar.

Mel isn’t just an observer, however, and Patterson reveals Mel’s investment in The Peerless Four patiently, sometimes even in moments where Mel seems unaware of how much her “objectivity” actually gives away. A runner herself, Mel feels the thrills and disappointments of the competitions, but her investment goes beyond that; unhappily married, the achievements of The Peerless Four become symbolic to her. It’s not an awakening necessarily, for Mel seems already awakened before the novel begins; however, as Mel’s objectivity begins to fall away, the novel seems to be about Mel’s freedom—freedom to feel what she wants, and to express it in her own way.

I mentioned before that The Peerless Four is cautious, which makes a certain degree of sense; after all, Mel is a cautious character. Yet sometimes the caution seems like Patterson’s, not Mel’s, as the author fears the reader missing the point, leading to statements like, “I began to confuse her story with mine,” or, “I’m the kind of spectator who longs to participate”; these are examples of Patterson’s caution, making sure aspects of Mel’s character are absolutely, positively clear. And by the end of the novel, didacticism sneaks in: “I thought about how women have struggled so long and resolute, and how our accomplishments carry a resonance of sacrifice, struggle, and elusive victor gained over incredible odds.”

The Peerless Four feels most persuasive when Patterson focuses on Mel’s perception of the athletes themselves. In those moments, the novel is unsentimental: Mel sees their physical prowess, yes, but also the flaws in their personal lives. Patterson finds little romance in competition, and even Mel—despite her love of running—has to confess that sports are “ridiculous. Meaningful and meaningless and all the while ridiculous, that equation of which outweighs the other dependent of temperament and perspective.”

When writing about sports, Victoria Patterson becomes an athlete: she does what she needs to do with strength and focus, and leaves her audience to search for meaning.