“Some days it seems […] that life holds important and beautiful stories. Other days, life isn’t shaped like that—into stories and whatnot.”

Aurelie Sheehan writes those words 18 pages into her fourth book Jewelry Box: A Collection of Histories, but she could have written them on page one. At first, those words and the story that contains them (titled “Story”) seem to add up to a mission statement—especially when the narrator, who is the author herself, announces what she hopes others will say about her: “Sheehan writes like a fucking maniac.” Bold, perhaps—but it’s a statement cloaked in fragility and uncertainty. It’s what she hopes others will say about her, not what she says about herself.

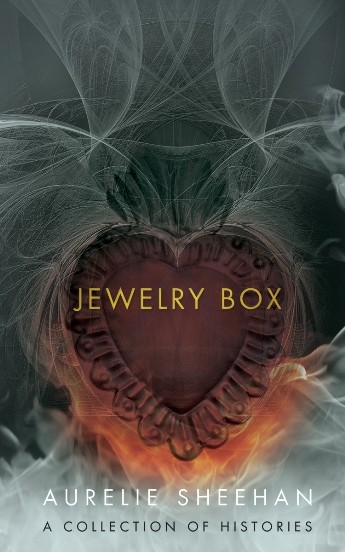

Jewelry Box is a 119-page collection of 58 stories, each titled after a different object, ranging from the general (“Talk”) to the specific (“Dishes the Cat Used, Now Stored in the Laundry Room”). Some of these stories are a paragraph long, others several pages. They veer from narrator to narrator. The effect of this book is dizzying. Reading it, I felt as though I had stepped into a room with 58 strangers and asked each of them to relay something personal. As a result, shards of these “histories” have lodged themselves in my mind, even if I have difficulty remembering the exact source of each image or phrase.

Jewelry Box is published by BOA Editions and released into a world of indie books where this sort of collection is somewhat familiar—think of Scott McClanahan’s recent Crapalachia; Amelia Gray’s AM/PM; Colin Winnette’s Animal Collection (whose publisher, Spork Press, first published many of Jewelry Box’s stories); and the hybrid works of Sheehan’s colleague at the University of Arizona, Ander Monson. These are hip literary references all, and Sheehan gestures toward the same whip-smart audience, concerned with the boundaries separating literary forms, the porous border between author and narrator, the fragmentary presentation of self, and lots of other stuff that people talk about in writing workshops.

The less-trendy influence of Raymond Carver also hangs over this collection, especially his shorter, odder stories like “Why Don’t You Dance?” and “Viewfinder,” which focus on surprising intimacy between strangers. (Consider, for instance, Sheehan’s “T-Shirt,” in which a young man accidentally encounters a girl with scoliosis as she undresses, her “terrifying back” creating a “powerful tenderness in him”—or the Carver-esque premise of “Telephone Call,” in which a married woman receives a surprise call from an ex-lover, while her husband sits in the other room, watching TV, oblivious.)

One of the strongest themes uniting this collection is the tension between crass, indifferent boys/men and the girls/women who enter their orbit—girls/women who are eager to please, to be loved, to fall into fantasy. Self-deception abounds, regardless of gender. What about the girl in “Suntan Lotion” who, trying to escape her life, allows a boy to spread the titular substance on her body, only for the boy to proceed directly to her thighs? Will she turn into “the young woman writer” in “Joke” who, while dining with her older male mentor (with whom she feels “semi-lost”), becomes fixated on the female desert chef’s confidence? Will this young woman writer eventually find herself in a relationship like the one in “Purse,” in which the man only calls her because he is “lonely and want[s] company, not because he in particular need[s] her company,” whereas “she wants him to care about it”—about a purse, about anything: Is this what will become of that young, semi-lost woman writer? Maybe she will get married, like the narrator in “Car Ride” who listens to the drone of family—her son’s questions about “cactuses,” her husband’s ramblings about basketball and bowling—when she wants only to understand her own feelings and be able to let them out. The narrator in “Rage” practices saying “I AM somebody,” and one gets the sense that many of Sheehan’s narrators need to do the same thing.

Of course, this is my own striving to make a coherent whole of Jewelry Box, but maybe that’s the wrong approach. “[A]lthough I cannot see the whole story,” Sheehan writes in “Book,” “at least I am embodying something familiar.” Maybe all these histories exist together to combat the idea that an author needs to see the whole story. Sheehan’s histories focus on moments, on objects, on fragments. We, the readers, do the rest, carrying through our days Sheehan’s embodiments of familiar things, letting our own minds and experiences fill in her ellipses.

Each of Sheehan’s histories reminds me of what she writes about the tulip in “Glass”: “it fucking grew even after it was cut.”